DRZEWIECKI: Familiarity with martyrdom.

Prof. Mario Agnes, Preface of Flavio Peloso - Jan Borowiec, Franciszek Drzewiecki, No. 22666: a priest in the prison camp , second edition, Borla, Rome, 1999, p.8-11.

FAMILIARITY WITH MARTYRDOM

"From its very beginning, my priesthood was written in the book of the great sacrifices of so many men and women of my generation." In this manner John Paul II described on page 47 of the book "Gift and Mystery", the type of "apocalypse" of our century that was the second world war, with its deathly succession of prison camps and systematic negations of human dignity.

The sacrifice of the Polish Christians is a remarkable and important dimension in the priestly vocation of Karol Wojtyla. He was 19 when the nazis arrived in his city of Cracow. These are his words: "That 1st of September will never ever be erased from my memory; it was the first Friday of the month. I had gone to Wawel for Confession. The cathedral was empty. It was, perhaps, the last time that I was able to go freely into that place of worship." ( "Gift and Mystery", p. 36).

That 1st of September 1939 changed the lives of Karol Wojtyla, the Polish people and the Catholic Church in Poland. The personal history of the young Karol, like that of every Pole, cannot be recounted without reference to that date. The years of the German occupation of Poland (1939-1945) were marked with arrests and transportation of Christians to the concentration camps. The names of these camps are sadly and painfully known, Dachau and Auschwitz, the "cathedrals" of human suffering and "capitals" of martyrdom.

These are the years in which the young Karol became aware of his priestly vocation, in the underground seminary that was the wish of the great Cardinal Adam Sapieha in Cracow. One of his seminary companions, Jerzy Zachuta, was not able to be ordained with Fr. Karol on 1st November 1946; one night the Gestapo had taken him away and shot him.

It was in this setting that Karol Wojtyla's generation was formed. This was the bloody reality of life in Poland. By means of mountains of corpses the Christians heroically bore witness to their faith in the Resurrection of Christ.

On 13 June 1999, in Warsaw, during his Apostolic Journey to Poland, John Paul II beatified 108 martyrs who had been killed by the nazis between 1939 and 1945. By this the martyrology of the Church of the twentieth century was enriched by 108 new heroes. Heroes of sanctity because they were heroes of history; heroes of history because they were heroes of sanctity.

In this new company of martyrs all states of life are represented: there are 3 bishops, 52 diocesan priests, 3 seminarians, 26 religious priests, 7 professed brothers, 8 professed sisters and 9 lay people. This is the proof that the hatred of Christians, the "odium fidei", was implacable. It is a jolt to the conscience to reflect that that persecution was immediately succeeded by another, of a different colour.

We remain stupefied before this kind of witness. These are stories that ask questions and force an examination of conscience. To read the words summarising the story of each one of them is an upsetting experience. There are no names as universally well-known as Maximilian Kolbe, Titus Brandsma or Edith Stein who have been canonised in past years.

Here, there is a generation of "unknown" Christians who continue to speak to each one of us. They speak with the clear voice of their consciences. They speak with the boldness of the truth and with their love of justice. They are not ghosts belonging to the past, nor are they locked away in history books that gradually gather dust on the shelves. These are people who remain alive because they have contributed in a decisive, even if often silent, manner to the making of history. They are not men and women of the past; they are men and women of the present and the future.

If humanity wishes to live in a world that is worthy, it must come to terms with the values for which these 108 martyrs gave up their lives. The witness of the martyrs must be jealously guarded and interiorised so as to enter, as true pilgrims, into the third millennium of the Christian era as we pass in full awareness through the Holy Door of the Great Jubilee of 2000.

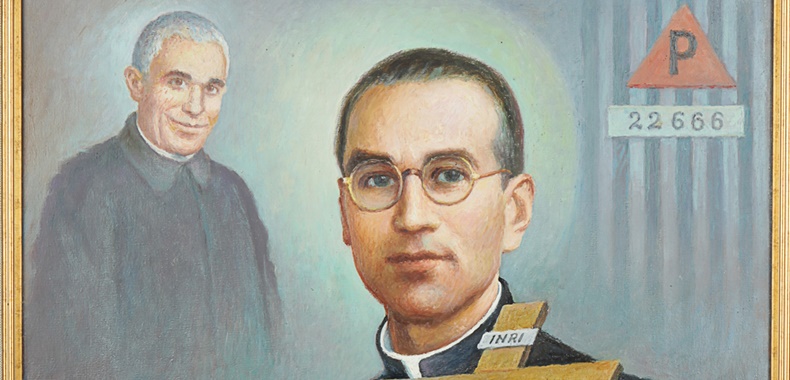

This book introduces one of the 108 Polish martyrs of the second world war: the Orionine Fr. Franciszek Drzewiecki. In the camp registers in Dachau he was a number: 22666. But he is a name that has been written in the "book of life" and engraved in the memory of countless witnesses who experienced his heroic charity. Now his name has also been entered into the list of saints venerated by the Church as models and intercessors. In those years marked by that whirlwind of folly, the dark night of the world was providentially pierced by exceptional witnesses of love. These 108 persons chose to believe in love because love has God's eyes.

In those years - thanks to the gift of John Paul II - we have learnt to know and love Poland. The book allows us to undergo an unpublished spiritual experience and to make a journey alongside a courageous and Christian people. In those years, thanks to the Pope "who had come from a far Country," we have all embraced and breathed the fervour of that Christian nation. We have come close to its history and taken part in building its future. Nowadays Poland is certainly a country that is much less "far away" than it was on 16 October 1978.

The Polish people are well experienced in suffering. They are fully aware that history should not be forgotten because there is no future without remembrance and no peace without remembrance. To remember does not mean to bear a grudge; it is rather a work of justice. To remember is to rebuild. To remember is to form the future.

This book, coming out at the end of a millennium, is something of a warning for the coming millennium. It reminds us that martyrdom has always been part of the life of the Church. The witness of the martyrs remains the most eloquent; they know this well in Poland. Throughout the centuries they have learnt to be familiar with martyrdom. The book has the merit of reminding everyone of this by means of the tangible history of men and women. Reading it, therefore, is truly a spiritual adventure.

Prof. Mario Agnes - Director of L'Osservatore Romano